If Democrats Don't Stop Fighting Each Other, Things Could Get Much Worse

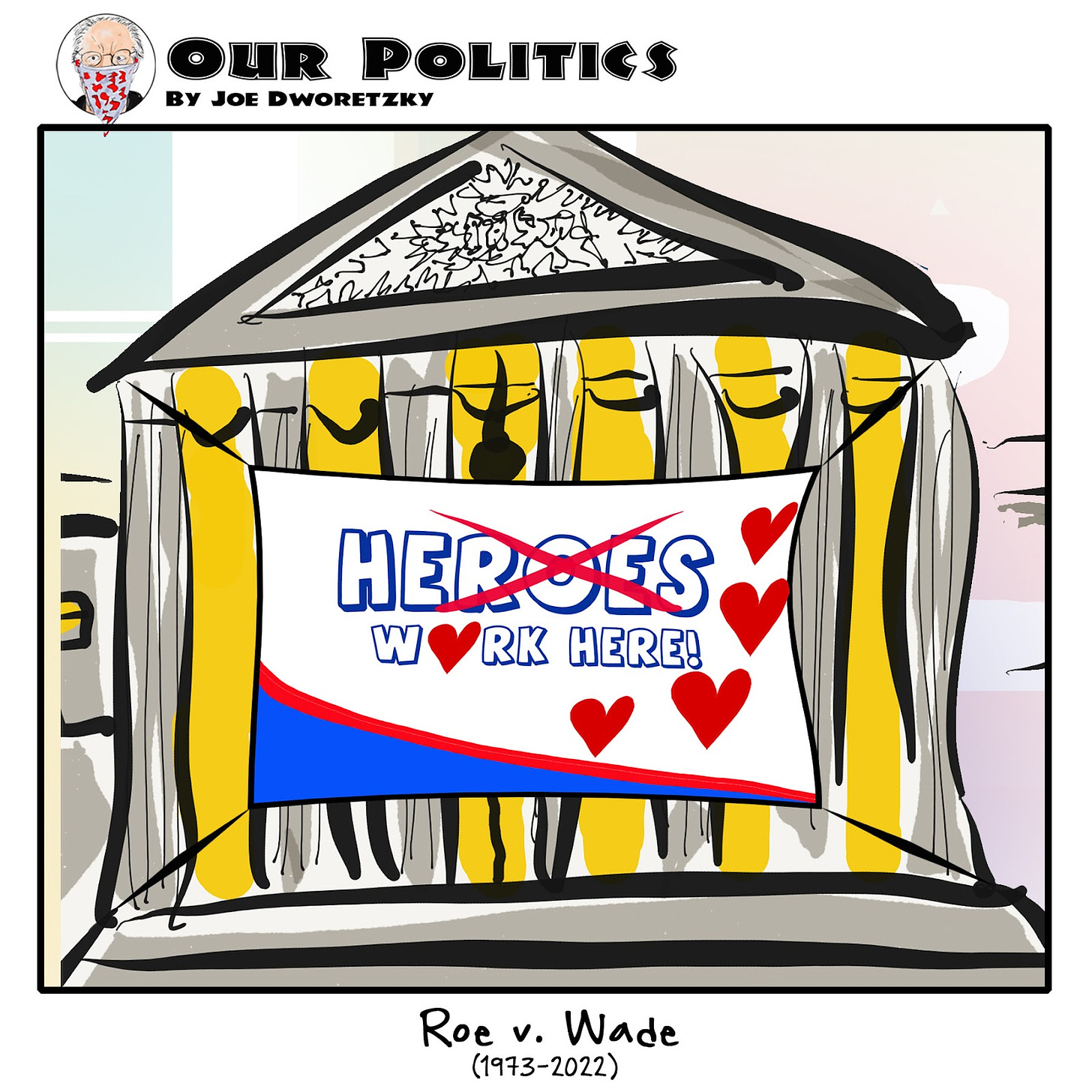

The Supreme Court dropped the hammer this week. While Samuel Alito’s draft opinion, along with the names of a majority of justices prepared to support it, had been leaked nearly two months ago, nothing could prepare people for the shock and pain that has reverberated across the country.

The question of where the Court, and the nation, goes from here remains to be seen. Now that anti-choice activists have achieved the essential first step in their 50-year-long effort to outlaw abortion, there is no reason to believe it ends here. The next battles will no doubt include state-level legislation criminalizing women who travel across state lines to get abortions, as well as prohibiting the prescription and delivery by mail of abortion pills.

And then there is the Holy Grail of Christian conservatives: passage of a federal “human life” statute or constitutional amendment that would broaden the definition of “person” under federal law to include the “unborn,” as early as the moment of conception. Should an embryo or fetus be deemed a “person” under federal law, abortion would become tantamount to murder, and laws enacted in liberal states protecting abortion rights would be rendered moot. In that event, there would be no safe havens, there would be no recourse; abortion would become illegal everywhere in the country.

This is a pivotal moment for the Democratic Party. For the better part of two years, Democrats in Congress have failed in their efforts to pass various iterations of Joe Biden’s legislative agenda. Progressives, in particular, yelled and screamed – most notably at Joe Manchin – and came up with all manner of excuses as to why they were not able to get anything done. Yet at no point have they looked in the mirror and considered the essential fact that from day one, they did not have the votes to pass the sweeping legislation of their dreams.

Counting votes is the most essential, elemental skill in democratic politics. I assumed that even if some members of Congress did not understand this, Joe Biden and his chief of staff Ron Klain surely do. I presumed that behind closed doors Joe Biden and Joe Manchin had quietly made a deal: that after Democrats tried to appease progressives by trying to get their multi-trillion dollar wish list passed, but failed because they didn’t have the votes, Biden and Manchin would get whatever they had agreed upon done.

Apparently they didn’t have a deal. Apparently, the problem Democrats have with basic political math reached right to the top.

The question, now that Roe v. Wade has been struck down, is whether Democrats are prepared to look in the mirror and realize that it is their own failure to heed the fundamental laws of electoral politics that has left them – and millions of American women – in the straits they find themselves in today.

Roe v. Wade was struck down, in part, because Republicans know how to count, and understand that at the end of the day, you can’t achieve anything unless you have the votes. Up until the presidency of Ronald Reagan, the Republican Party was a broad-based coalition of generally small-government conservatives and fiscally conservative moderates that was welcoming to politicians with a range of views on taxes, abortion, and guns, among other issues.

That all changed in the 1980s. In the wake of the Reagan Revolution, GOP strategists identified a discrete number of single-issue voting groups that the party would cater to going forward to drive voter turnout. The strategy was straightforward: as long as Republican candidates would swear fealty to those core issues – most notably anti-abortion, pro-gun, and anti-tax – those candidates would be assured that those single-issue voters would show up on Election Day, regardless of what other stances a candidate might hold.

The execution of the strategy was not as simple as it might seem, as it required political maturity on the part of those voters. Anti-abortion voters, for example, were often vehemently opposed to trade with China, due to treatment of Chinese Christians by the Communist Party. Yet anti-abortion groups and their voters consistently kept their eyes on the prize, turning out for anti-abortion Republican candidates that supported trade with China along with those that opposed it. They understood, decade after decade, that they could not – in their eyes – let the perfect become the enemy of the good.

The defeat of George H.W. Bush for a second term in 1992 after he violated his no-tax pledge has stood for the past 30 years as the object lesson to Republicans of the consequences of failing to toe the line, while the election of Donald Trump a quarter century later proved to be the defining example of the effectiveness of the Republican strategy. Trump, a man with few notable personal convictions, embraced the Republican single-issue voter playbook with a vengeance. He swore as he campaigned in 2016 that his tax cuts would be the largest ever, that his support for the NRA would not waver, and that his Supreme Court nominees would overturn Roe v. Wade. And he delivered.

It has become a truism of sorts that activists on the left and the right control the political parties. And while that may in large measure be true, it has widely differing implications for Democrats than it does for Republicans. For the GOP, fealty to Christian conservatives, gun rights activists, and anti-tax voters has been part and parcel of an intentional Election Day turn-out strategy that has succeeded in building a degree of Republican political power at the federal, state, and local level that far outstrips what raw demographics might appear to dictate.

For Democrats, in contrast, political activism on the left has rarely been accompanied by a commitment to turn out on Election Day for whomever the Democratic Party might ultimately nominate. Indeed, George W. Bush and Donald Trump each likely won the presidency on the backs of progressive voters who succumbed to Ralph Nader’s “Tweedledee vs. Tweedledum” assessment of democratic politics, and either stayed home, voted independent or voted Republican out of spite.

This year, even as the prospect looms of Republicans not simply winning back majorities in the fall, but toppling of the democratic process itself two years down the road, we see articles and hear comments about this group or that group that may not show up in the fall should Joe Biden or Democrats in Congress not deliver whatever it is they care about before Election Day. The fact that Democrats might not have the votes does not seem to matter.

Unlike Republican voting groups that have stayed the course for decades to achieve the victories that they won this week on guns and abortion, too many within the Democratic Party remain only too willing to cut and run if they don’t get what they want, when they want it.

But the Democratic Party problem runs far deeper than its failure to pass legislation during the current term. As former Obama pollster David Schor has argued since the 2020 election, Democrats are increasingly losing ground among mainstream, working and middle class voters – of all races – as the discourse within the party increasingly reflects the language and issues of highly educated elites. “That’s really dangerous,” Schor observed in an interview last year, “because in the Democratic Party, if you don’t have non-white conservatives, and you’re just a party of educated, white liberals, that gets you to 25%-30% of the vote.”

And the situation only looms to get worse. The emergence of inflation, and the increasing likelihood that we are heading into a recession, is only increasing the distance between party elites – who continue to be focused on issues surrounding racial justice, climate change, gender and sexuality, and identity politics – and the broader electorate that is overwhelmingly concerned about the economy and crime. Those in the party who ignore the chasm that now separates them from many in the country do so at their peril.

This should be a road to Damascus moment for Democrats. For 40 years, Republicans treated every election as though Roe v. Wade itself was on the ballot, while too many Democrats, so often caught up in one internecine feud or another, failed to grasp the urgency of the moment.

Perhaps – just perhaps – even as frustration over Roe is at a boiling point, and rage is pushing activists to accelerate their threats of retribution against a Democratic Party that has limited options to address the Court ruling, the shock of waking up in a post-Roe world will be enough for those who have argued over the years that there is no difference between the two parties to realize their own culpability for the Supreme Court decision this week. Perhaps, even as tempers flair, those in the party who have routinely vilified Joe Manchin and other political centrists will realize it is time to sheath their daggers.

Through its decision, the Supreme Court has shaken the political equilibrium of the country and offered Democrats an opportunity to chart a new course. If Democrats hope to respond to the Roe decision and protect abortion rights for women across the country, they will need to compete more effectively than they have in years at the state and local levels where the coming battles will be fought, and they will have to win back voters that they have alienated. If Democrats hope to win those battles, they will need to start, as a unified party, by looking to Democrats who serve effectively in red states and districts, as models of how they might work to restore trust in their party across the electorate.